A strategic solar energy boom is afoot in Eastern Europe

Against the spectre of Russian aggression, renewables are in

A revolution, of sorts, is unfolding in Eastern Europe. The solar energy rollout there is accelerating at a blistering pace. I’ve noted before how Poland (arguably better described as a Central European country today) is installing solar panels faster than the UK – despite having a much smaller population, and less than half the GDP per capita.

The figures for solar deployments in 2024, for example are: the UK at 2.3 gigawatts; Poland at 4 gigawatts. Though it’s important to note that Poland is still heavily reliant on coal for electricity generation, which the UK is not.

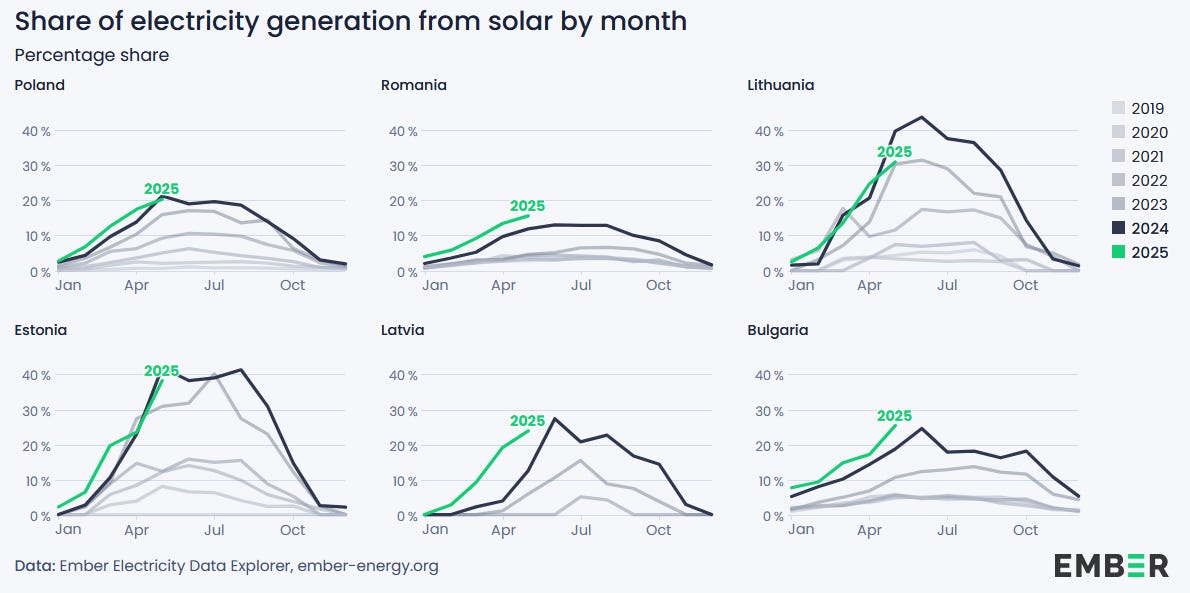

Other nearby countries are also increasingly turning to solar energy. Let’s look at data from Ember, the energy think tank, to build up a picture.

What’s striking here is the sizeable gaps between those horizontal lines, with each successive year during the last six years revealing a significant increase in solar’s share of overall electricity generation in those countries.

Lithuania and Estonia stand out as nations that are now reasonably close to generating half their electricity from solar energy during the summer months.

Sun worshippers

This makes sense. A recent analysis that estimated the potential contribution solar energy could make to power systems in various European countries found that parts of Estonia, Latvia, Romania and Hungary, for example, have roughly as much potential as parts of sun-baked Spain and Portugal.

And that potential was a function both of energy demand in those countries as well as how much land was available for solar installations.

“Many territories – especially in Spain, Portugal and Romania – could produce 30 times or more the energy required, becoming major energy exporters,” the authors noted.

As Reuters highlighted recently, the combined capacity of solar energy in nine key Eastern European countries increased by 450% between 2019 and 2024 – from 9 gigawatts to 46 gigawatts. That’s much faster than solar capacity has risen in the rest of Europe.

How much is all of this activity a reaction, specifically, to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which began in 2022? “[Russian President Vladimir] Putin has made the EU look at alternative sources, and among that [is] renewables,” says Mitchell Orenstein at the University of Pennsylvania. Orenstein is a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a think tank.

Other observers agree. We know, for example, that Europe has sought to diversify its energy sources in response to Russia’s behaviour, chiefly by moving away from Russian gas and oil. Plus, earlier this year, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania completed their switch away from the Russian electricity grid, joining the European Union’s (EU) instead. Eastern European nations have bolstered interconnector links with one another during the last few years, also.

EU countries in general have reduced their reliance on Russian fossil fuels and lowered energy consumption in certain areas to assist with this transition. But, notably, “solar has been the big success story”, says Orenstein.

Strategic resilience

In 2023, Orenstein published an in-depth article on the energy transition in Europe following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Two years later, I ask how he views the situation: “The movement away from Russia is still accelerating, absolutely,” he says.

But while electricity generation is greening, decarbonising transportation and buildings is notoriously more difficult – Latvia provides an interesting case study there, according to this report from the International Energy Agency.

Given the overall trend, though, Orenstein hinted in his article that Putin might go down in history as an unintentional “hero” of green energy. When I question whether that choice of language would sit well with people in Eastern Europe, Orenstein replies, “It’s been hard to convince any country really to get off fossil fuels.” To paraphrase, he suggests that it has arguably taken the shock of the invasion to force the issue.

Renewables can help countries assert energy independence, Orenstein explains. And while there are vulnerabilities and weaknesses within all these technologies – you only need to cut a few cables to put an offshore windfarm out of action, for instance – in principle, they offer a greater level of resilience by being so distributed. Solar especially “tends to be a lot more decentralised”, says Orenstein. “It’s hard to knock out.”

And that could soon be important. Some countries are openly preparing to face down possible Russian aggression.

Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania have stepped up their defence spending – with the latter also unveiling an evacuation plan for its capital, that would take effect in the event of a Russian invasion. Poland has introduced mandatory firearms training for school children and Romania has said it will increase the size of its army.

‘We are moving on’

Energy independence appears to be a key part of this defensive strategy towards Russia. Just take a look at the language of Baltic states politicians upon switching over to the EU’s electricity grid: “We will never use [Russia’s grid] again. We are moving on,” said Latvia’s energy minister at the time. “We are leaving the aggressor without the option of using energy as a weapon against us,” added Estonia’s foreign minister.

All of this goes to show that the push for resilience, and lower emissions, in the face of climate change can have diverse motivations. In countries deeply concerned about coming war, that concern has clearly had a galvanising effect. Other factors are at play too, including the EU’s net zero targets. But the extent to which a nation sees such manoeuvres as necessary, or urgent, can vary.

“The EU states that border Russia and Ukraine, by and large, have done a really good job of ensuring energy security,” adds Orenstein. “Western Europe is more of a laggard.”

Further reading on this week’s story

The EU’s report on the potential for significant further solar energy deployments is packed full of detail.

Despite being in the middle of a devastating war with Russia, Ukraine managed to install 0.8 gigawatts of solar panels in 2024, according to the Solar Energy Association of Ukraine.

The growth of wind and solar energy in the EU since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has saved $13.8 billion in energy costs, due to a reduction in fossil fuel use, says Ember.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this story, don’t forget to share it with your friends and colleagues. You can also subscribe to The Reengineer and follow me on Bluesky.

Update: Clarified the description of Poland, which is now more commonly described as being in Central Europe.

Interesting read, thanks for putting it together.

What is the data source for the map showing potential renewable energy production? It shows some areas in windy northern Germany with very low potential while they already produce more electricity than they use.

Regards,

Jan