Hot air: the bizarre effects climate change could have on radio

From lost signals to super long-distance broadcasts

One minute it was a British radio broadcast booming out of the studio speakers – then it suddenly switched. To Italian pop. Quentin Nield was then, during the late 1980s, working as a radio broadcast engineer for a commercial radio station.

“I remember the calls coming through from the programme saying, ‘What the hell’s going on?’,” he says. “We couldn’t believe it. We were looking at each other going ‘No!’.”

It was, apparently, a case of “sporadic E”. A phenomenon in which weird goings on in Earth’s atmosphere allow radio signals to travel much further than normal. In this instance, an Italian radio station using the same frequency as the British radio station had suddenly – and quite unintentionally – usurped its broadcast. Nield and his colleagues were powerless to intervene. “There’s nothing we can do – we’re stuffed.”

But here’s the really crazy part. There’s a chance that the frequency of freak events like this could be affected by Earth’s changing climate. While the causes of sporadic E events are mysterious, some researchers think that changing wind patterns in parts of our planet’s atmosphere might trigger sporadic E incidents in the future.

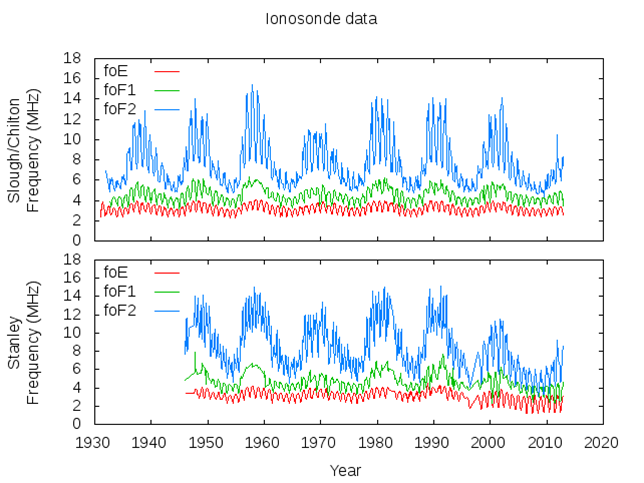

It’s also the case that Earth’s ionosphere is gradually lowering in height (on average) over time, as a result of rising carbon dioxide levels. Because some radio equipment bounces signals off the ionosphere to achieve broad coverage, this lowering of that atmospheric ceiling means said signals don’t propagate quite as far as they used to.

It’s worth saying that these fluctuations are fairly subtle. We’re talking sub-percentage point changes over the course of decades, in most cases. Nobody’s radio is going to explode because of climate change (though a few might melt). But where impactful anomalies and, perhaps, sensitive communications are concerned, even slight variations in radio propagation can really matter to people.

So, now we have a hunch that a climate signal could be broadcasting, perhaps it’s time we tuned in.

“It’s a bit like going fishing,” says Jim Bacon, retired meteorologist and amateur radio enthusiast, referring to sporadic E. While detested by commercial radio engineers who want to keep their stations broadcasting and their advertisers happy, amateur or ham radio operators love it. Sporadic E means you might suddenly be able to make contact with someone hundreds or even thousands of kilometres away, when that wouldn’t normally be possible with the same equipment.

Bouncing back

Bacon explains that such events depend on changes in the ionosphere, a section of the planet’s atmosphere roughly 80-600km above ground-level. The ionosphere contains atoms and molecules, which sometimes become charged, or ionised, creating layers of electrons. Those electrons can reflect radio waves back down to Earth. But where exactly electrons emerge in the ionosphere and at what densities depends on a range of factors – including solar activity. The E layer of the ionosphere doesn’t usually reflect radio waves but now and again (sporadically), it can.

Such occurrences are not just curiosities. So significant are sporadic E events that the US Air Force has developed ways of tracking them because such intelligence could, for example, help radio operators continue to transmit and receive during disasters.

No-one knows exactly what triggers heightened reflectivity in the E layer – it’s likely a confluence of factors – but one idea is that high-flying winds play a role. They might help bring charged particles in the E layer together, like “beads on a string”, making that layer capable of reflecting radio waves, says Chris Scott at the University of Reading: “When you have wind shear above and below it, you push them together.”

Could climate change affect that? “It’s a perfectly reasonable hypothesis,” says Scott. And one that scientists in the UK are currently investigating. The Reengineer has heard from researchers working on projects in this vein at the University of Leeds and the University of Birmingham. “We anticipate a subsequent impact on sporadic E […] however, the exact nature of that impact is not yet known,” says David Themens at the University of Birmingham.

Bubble trouble

Themens adds that climate change could also influence the formation of plasma bubbles – areas of irregularity in the equatorial ionosphere, which can be severe enough to disrupt or even block radio transmissions.

In 2022, the largest recorded plasma bubble event occurred following the eruption of the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai submarine volcano in the Tongan archipelago in the southern Pacific Ocean. The plasma bubble it created was big enough to severely disrupt GPS satellites and other radio communications.

Storm activity can also influence the formation of plasma bubbles by propelling atmospheric waves into the ionosphere, says Themens. And so climate change, which affects storm strength and frequency, might conceivably heighten the risk of plasma bubbles.

Separately, a 2022 paper suggested that rising carbon dioxide levels could also make plasma bubbles more common over time. “To my knowledge, this paper is among the first that points out this possible connection,” says Kornyanat Hozumi at the University of Scranton in the US, though she adds that further study could help verify the relationship of carbon dioxide to plasma bubble occurrence.

Signalling in the rain

Other weather effects could also have an impact. Researchers in Nigeria published a paper in 2021 that described how climate change-affected rainfall could disturb radio communications in the country. Rain fade is a phenomenon in which radio waves find it difficult to pass through heavy downpours. “My first radio station, we were on FM and AM,” recalls Nield. “Especially during thunderstorms, the AM signal was almost unlistenable.”

Nield, who now teaches audio, radio and podcasting at Goldsmiths, University of London, says that, should climate change-related radio disturbances become common enough to cause problems, it might simply hasten the move away from traditional forms of radio such as FM and AM. “I feel it would just drive more people to online-only,” he says.

While some parts of the world are already well into that transition, not everywhere is. AM radio is still popular in many developing countries, for example and, in general, traditional forms of radio are still considered highly resilient. They are the go-to option during disasters.

Bacon cautions that it is difficult to lay radio propagation anomalies conclusively at the door of climate change over, say, seasonal or cosmic variations. But if we do discover any operationally significant climate impacts, such knowledge might one day help engineers protect the integrity of emergency transmissions in disaster zones; stabilise GPS signals; or fortify broadcasts from the trendiest radio stations pumping out banging tunes.

It’s not just academic researchers who might collect important pieces of the puzzle, either. In 2023 and 2024, amateur radio operators helped to track the subtle effects of solar eclipses on radio propagation, which makes me wonder whether there could be a role for such enthusiasts in documenting what climate change might be doing to radio in the coming years.

Jim Bacon, for one, doesn’t want to miss out on the action. When it comes to sporadic E in particular, he says, “People like me will be on the bands at the right times – to capture more of these events.”

Further reading on this week’s story

Last year, StateTech magazine published an interesting feature on the role of radio communications in a climate change-altered world.

A 2024 review explored the various ways in which climate change could parts of the Earth’s atmosphere, including the ionosphere.

Chris Scott published a blog on climate change and the ionosphere in 2022 and has covered this topic in academic papers, too.

Radio is always changing. In 2023, I wrote about the demise of once-popular longwave radio, which is used only in a handful of countries now.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this story, don’t forget to share it with your friends and colleagues. You can also subscribe to The Reengineer and follow me on Bluesky.