Noisier take-offs, engine wear – planes are flying into climate change

Emissions-spewing aircraft are far from immune to global warming

A roar of engines overhead. Awake again. “The planes never used to be so loud round here,” a troubled sleeper may reflect in the year 2050. Two or three decades from now, aircraft noise could afflict thousands more people who live near airports – because of climate change.

Noise from commercial planes is more than a nuisance. It can raise the risk of heart attacks and strokes, and affect children’s performance in school.

As global temperatures rise, warm air – being less dense than cool air – is reducing the amount of lift that aircraft wings generate.

For several years, a group of researchers in Europe has studied this phenomenon. Early on, they realised that a “warmer air, reduced lift” scenario might mean planes having to travel further down runways before being able to take off.

“With the take-off distances increasing, airliners would be inclining away from airports more shallowly,” says one of the group, Guy Gratton at Cranfield University in the UK. “You get a bigger noise footprint.”

Compared to today, thousands more people could be hit by relatively high levels of aircraft noise as a result. “It matters a lot if you happen to be one of [them],” says Gratton.

The aviation industry faces heavy criticism over its contribution to global emissions (roughly 3%, depending on how you crunch the numbers). However, aviation is itself far from immune to climate change. Pilots and passengers are almost certainly going to become more cognisant of climate change-related impacts on flying during the coming years.

Hot wings

Gratton, who holds commercial pilot licences, explains that climate change is raising the top of the troposphere – the lowest layer of Earth’s atmosphere – and making it warmer. Plus, some areas, including the poles, are getting hotter a lot quicker than others. These changes are among those that ultimately affect aircraft operations.

“Pretty much everywhere, the climb-out will get shallower, which means more people around the airport [will experience] unpleasant noise levels,” Gratton says. In a study published last month, he and colleagues calculated that the climb angle for an Airbus A320 flying out of one of 30 airports in Europe could reduce by 1-3% on average, though it could drop by as much as 7.5% on very hot days in the most extreme climate change scenarios.

It’s possible that, by 2050, the number of people living near airports who experience 50 decibels of noise or more could rise by up to 4% – as many as 2,500 individuals in the most densely populated locations.

“We do get a lot of scepticism,” says Gratton, who notes that the effect he and his colleagues describe is expected to emerge over the course of decades. The actual numbers of people who experience increased take-off noise may also be modified by the emergence of new aircraft, new technologies, and new airports.

A doctoral thesis published in 2023 found that the required increase in take-off thrust between now and 2100 was small – averaging 0.3%. Though the author, Thomas Pellegrin, added, “Significant deviations from the mean were observed at climatic outlier airports, including those located around the Siberian plateau, where take-off operations may become more difficult.”

Militaries are already considering impacts on payload, however, because reduced lift means their planes and helicopters might not be able to carry quite as much cargo. Climate change also increases turbulence, which at its most extreme can be deadly.

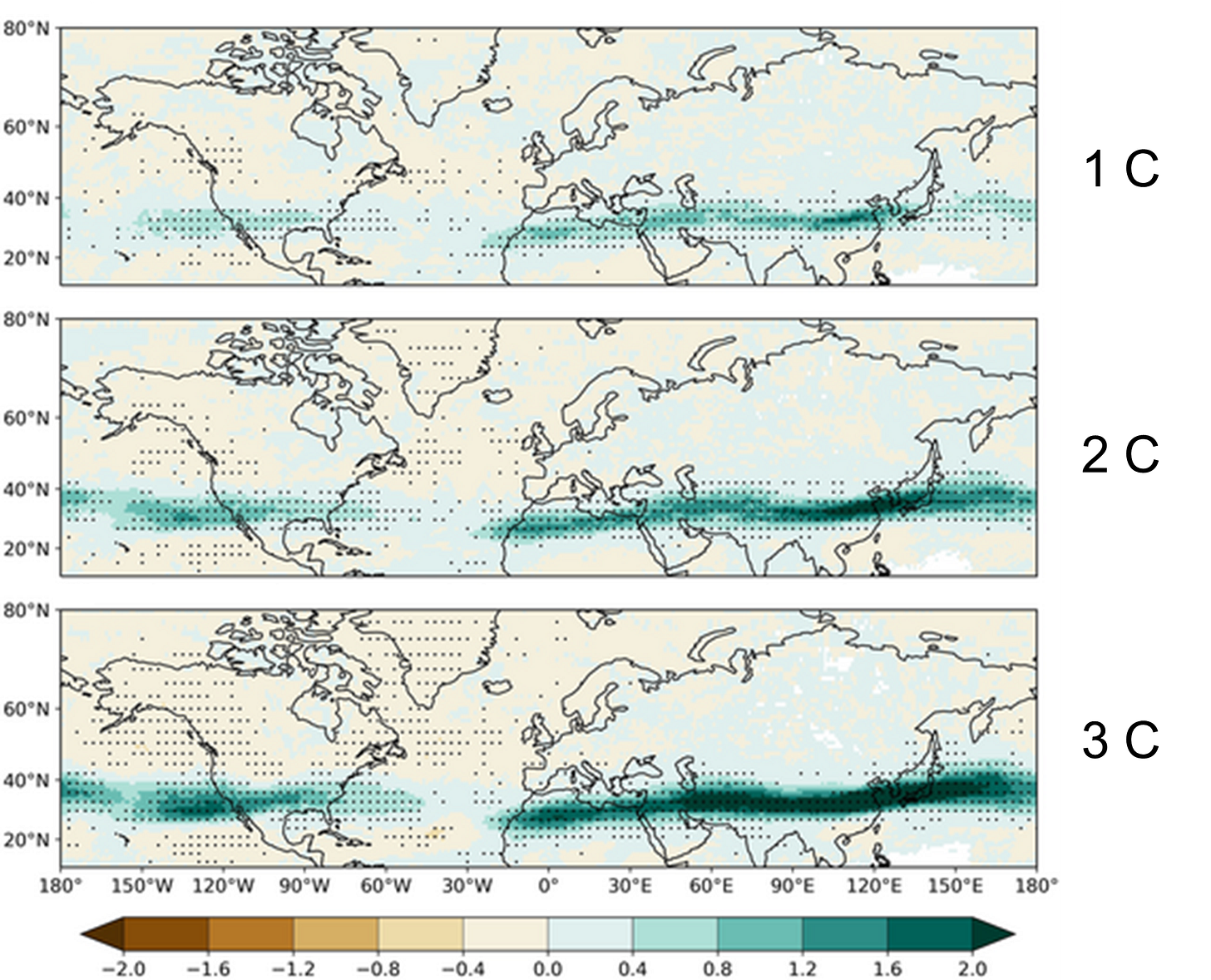

This happens due to greater temperature differences between air to the north and air to the south of the globe. In some regions, pilots can expect faster jet streams and more frequent vertical wind shears. Weather-related disruptions to flights, in general, are also rising at present.

Last year, Pellegrin published an online dashboard plotting the expected change in surface temperature, by the year 2100, at dozens of airports around the world. He says rising temperatures have implications not just for take-off performance but also for water supplies used to cool terminal buildings, equipment maintenance and the health and safety of ground staff.

Engine trouble

Separately, a study published last year reported data from a real commercial airliner – a Boeing 787-8. The data revealed that when the plane flew at 38,000 ft (11,600m) through warmer air during the summer months, it produced exhaust gases that were, on average, 200C hotter than expected based on “standard atmospheric values”. Global warming, the authors say, is to blame for the high figures.

“Such elevated temperatures are likely to accelerate the degradation of turbine components, resulting in increased fuel consumption,” they note. That could raise engine maintenance costs and potentially reduce the lifespan of these complex machines.

A very small proportion of the world’s population flies – and an even smaller group is responsible for a disproportionately large chunk of flying-related emissions. I point out to Gratton that, given aviation is partly to blame for climate change, there are some who would argue that all these impacts are good reasons to fly less overall.

“The right answer has got to be somewhere in the middle,” he says, referring to the spectrum between banning all flights and carrying on with business as usual. Many businesses and communities depend on aviation, he adds, asserting that reducing aviation’s impact on the planet will require a “complex balancing act”.

But, clearly, climate change has serious implications for aircraft, passengers, and even people who never fly but who happen to live near airports. Exactly how this will all play out in the coming years remains wrapped in cloud.

“I’m still acutely aware,” says Gratton, “of how little we know.”

Further reading on this week’s story

Aircraft cause global warming through carbon emissions – but also through the production of contrails, which having a warming effect under certain conditions. Hannah Ritchie explains more in her latest newsletter.

What would it mean if we cancelled all flights, forever? This video from the BBC ponders that question.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this story, don’t forget to share it with your friends and colleagues. You can also subscribe to The Reengineer and follow me on Bluesky.