Church organ tuning records mirror our warming climate

The records appear to reflect climate change, as well as the increased heating of churches in winter

Yangang Xing had never heard of organ tuning books. But his colleague at Nottingham Trent University, Andrew Knight, regularly played the pipe organ at churches as a teenager.

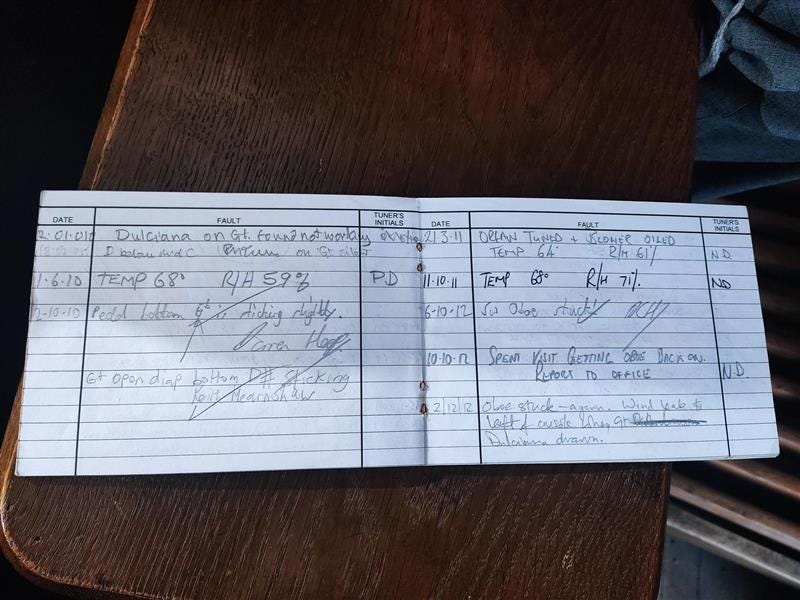

When they set out to study how environmental conditions in churches had changed over time, Knight explained that, all over the country, many organs have notebooks full of data tucked away in their recesses.

“I would sit at the organ between hymns, or between weddings,” says Knight. “Quite often, the only thing to look at between services was this little red book that sat in the corner.”

‘Goldmine’

Xing realised that organ tuning books were troves of data, which might span many decades. “We said, ‘Oh, this is a goldmine’,” he recalls. “We could really dig into it.”

Organ tuners make brief records of their visits and often jot down observations, including the temperature and humidity inside the building.

This is because various materials and moving parts inside organs are sensitive to climatic changes. They warp and shift as the church is heated, or as the weather seesaws outside. Knowing the conditions under which an organ was last tuned aids the next tuner who visits.

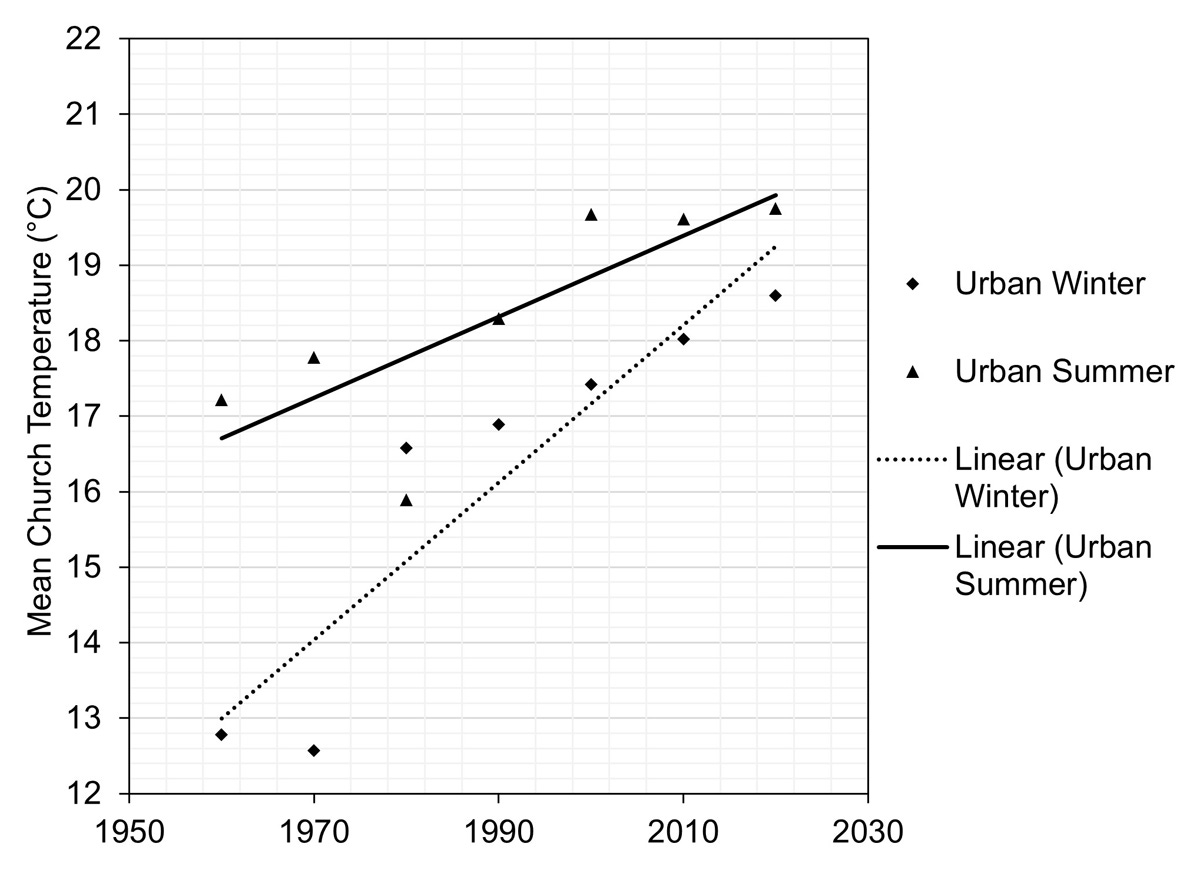

Earlier this month, Xing, Knight and their colleague Bruno Bingley published a paper in the journal Buildings & Cities, which describes preliminary data gleaned from 18 organ tuning books. These records were sourced from churches in London, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire and date back to 1966. They indicate a rise in average temperatures inside churches since then, during winter and summer periods.

It reflects that churches are being heated, artificially, to higher temperatures than was common in the past but also that these old buildings are getting warmer even in summer months when heating systems are likely turned off. This is a “hint” of climate change, says Knight.

The average summer temperature for urban churches in the organ books sample was 17.2C during the late 1960s. By the 2020s, it had reached 19.8C.

“It quantifies what we’ve seen,” says Andrew Scott, managing director of Harrison & Harrison, a Durham-based firm that builds and services pipe organs. “We’re definitely seeing a rise of internal ambient temperature through the unheated summer months due to rising temperatures outside.”

He mentions one chapel in Cambridge that has particularly large stained glass windows. Scott describes it as “basically a giant greenhouse” that gets noticeably warmer than usual on sunny summer days. The precise fabric of each building can affect thermal fluctuations.

You might also enjoy:

Let there be warmth! The British churches putting their faith in heat pumps

Why the world’s most potent greenhouse gas was released in a London Tube station

Hot air: the bizarre effects climate change could have on radio

The organ tuning records could be useful for climate studies, says Neil MacDonald, professor of geography at the University of Liverpool. “As somebody that’s worked on a lot of historical records of climate and weather, I’ve never come across this,” he says. “I was fascinated, actually.”

It is possible that summer temperatures in churches might be influenced by factors besides climate change, he notes. Some churches could have been ventilated more frequently in years gone by, for example.

Climate-ready organs

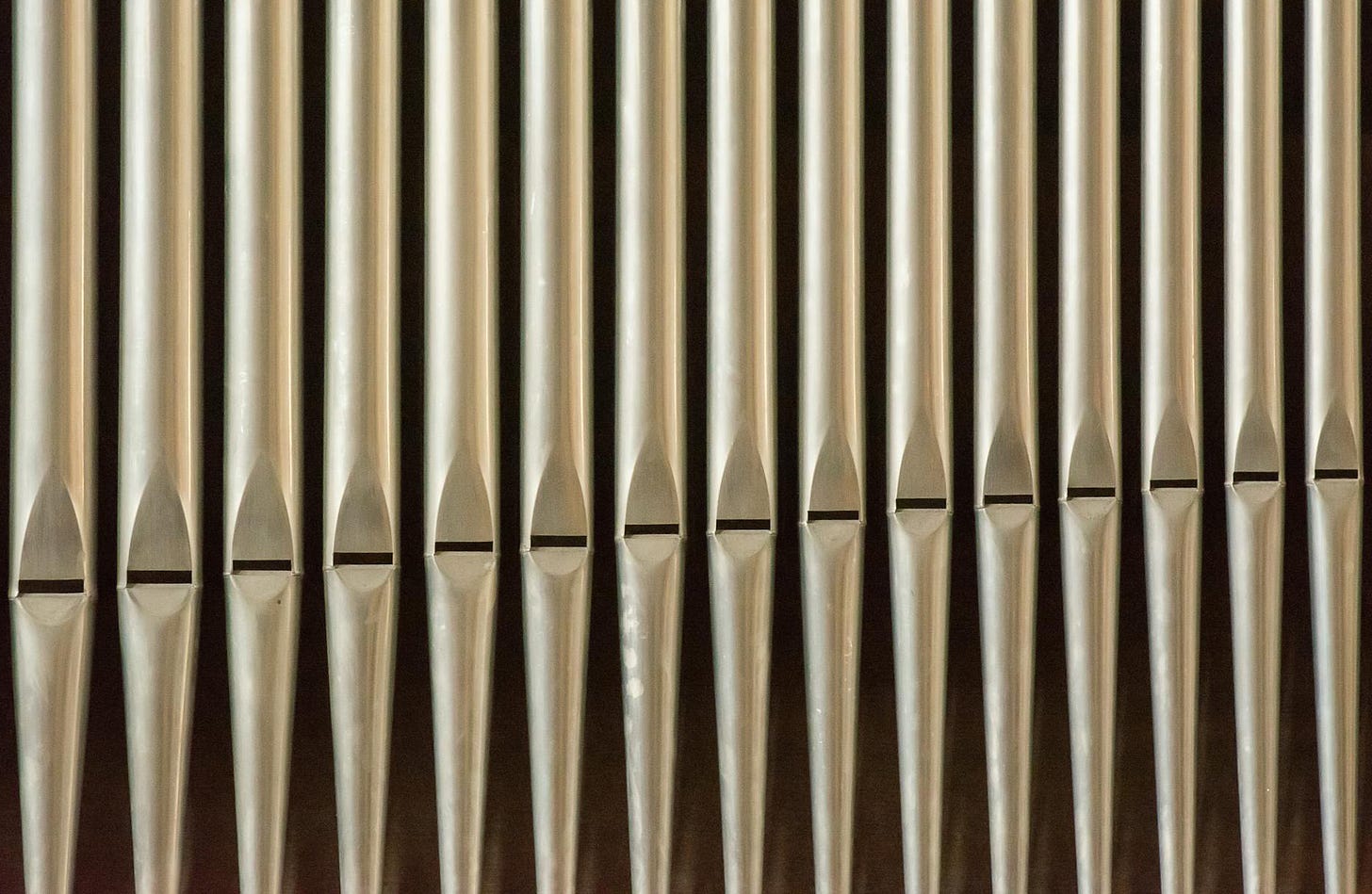

Organ tuners care about temperature because it affects the expansion and contraction of materials such as wood and metal, commonly used in organs, Scott explains.

Humidity plays a role, too. One of the remarks left by a tuner and noted by the researchers in their paper regards a church organ in Nottingham. Part of the instrument appeared slightly damaged and more difficult to tune than last time. “Weather? Misty,” the tuner wrote, appearing to ponder the cause.

Very old instruments that contain oak are particularly sensitive to climate. When building a new organ today, Scott says his firm selects materials that would not be so severely affected by swings in temperature and humidity. (He cautions that warmth is not the only reason why faults might develop in an organ – natural degradation of materials, a lack of proper maintenance and other factors could also play a role.)

While many churches are large, difficult-to-heat, stone buildings – making them refuges for some during heatwaves – the impact of hot summer weather can still be enough to trouble an organ. A change of just one degree Celsius may alter the pitch of one of these instruments by 0.8 hertz, says Scott.

That means if an organ is tuned at, say, 16C, and then the temperature later rises to 20C, the notes the instrument produces can be perceptibly different.

Besides weather, powerful heating systems installed in churches are likely to affect pipe organs even more profoundly, says Scott. Forced air heating technology, which blows a stream of warm, dry air into buildings, raises indoor temperatures quickly and is therefore especially troublesome for organs, he adds.

Xing and his co-authors write that campaigns to heat up churches and other community buildings, in order to help people who are experiencing fuel poverty during winter months, are “a positive social development”. However, this activity risks detrimental effects on old buildings and their facilities, including organs.

Going to extremes

Scott’s firm has tuned organs all over the world, including in Nigeria, Malaysia and India. He says in countries with very hot climates, keeping an organ in tune is especially challenging. It’s so hot in some of these places that certain glues traditionally used to bond together parts of an organ would “go off”, says Scott. This means organ builders there have had to use alternatives or combine glues with other ways of binding together parts, such as lashing.

As the climate heats up further, tuning and servicing organs in such countries will probably only get more difficult. MacDonald says that organ tuning records from around the world could even help to expand our understanding of how the climate has changed in places where more formal gathering of meteorological or climatological data has been less common, historically speaking.

Xing says he and his colleagues hope to analyse more organ tuning book data in the future and he urges anyone who owns such records to get in touch with him. “If we can find older ones, it would fascinating,” he says.

Scott says that his firm has records dating back perhaps as far as the 1930s, which he suggests could be useful to Xing and his fellow researchers. “We would be very happy to collate that data,” he offers.

For Xing, this research has revealed how valuable environmental data is sometimes hiding in surprising places. “I hope people realise the value of tuning books,” he says.

Further reading on this week’s story

Climatological and weather data can be found in all kinds of unusual archives. Climate scientist Ed Hawkins, of the University of Reading leads Weather Rescue, a series of citizen science projects, which ask volunteers to help digitise old weather records. This has included logbooks from historic warships.

In 2023, I wrote about a separate project to gather historical weather data from school logbooks in the Outer Hebrides.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this story, don’t forget to share it with your friends and colleagues. You can also subscribe to The Reengineer and follow me on Bluesky.