The big cover-up: ‘We should bring back old habits of shading windows’

Shutters and awnings can cool properties down, and look good, too

The idea flowed to him across time – delivered on a set of postcards. Urban designer Clément Gaillard was in the French city of Arles, looking for ways of protecting buildings from heatwaves. And, in one of the city’s archives, he found an old book of postcards that triggered his imagination.

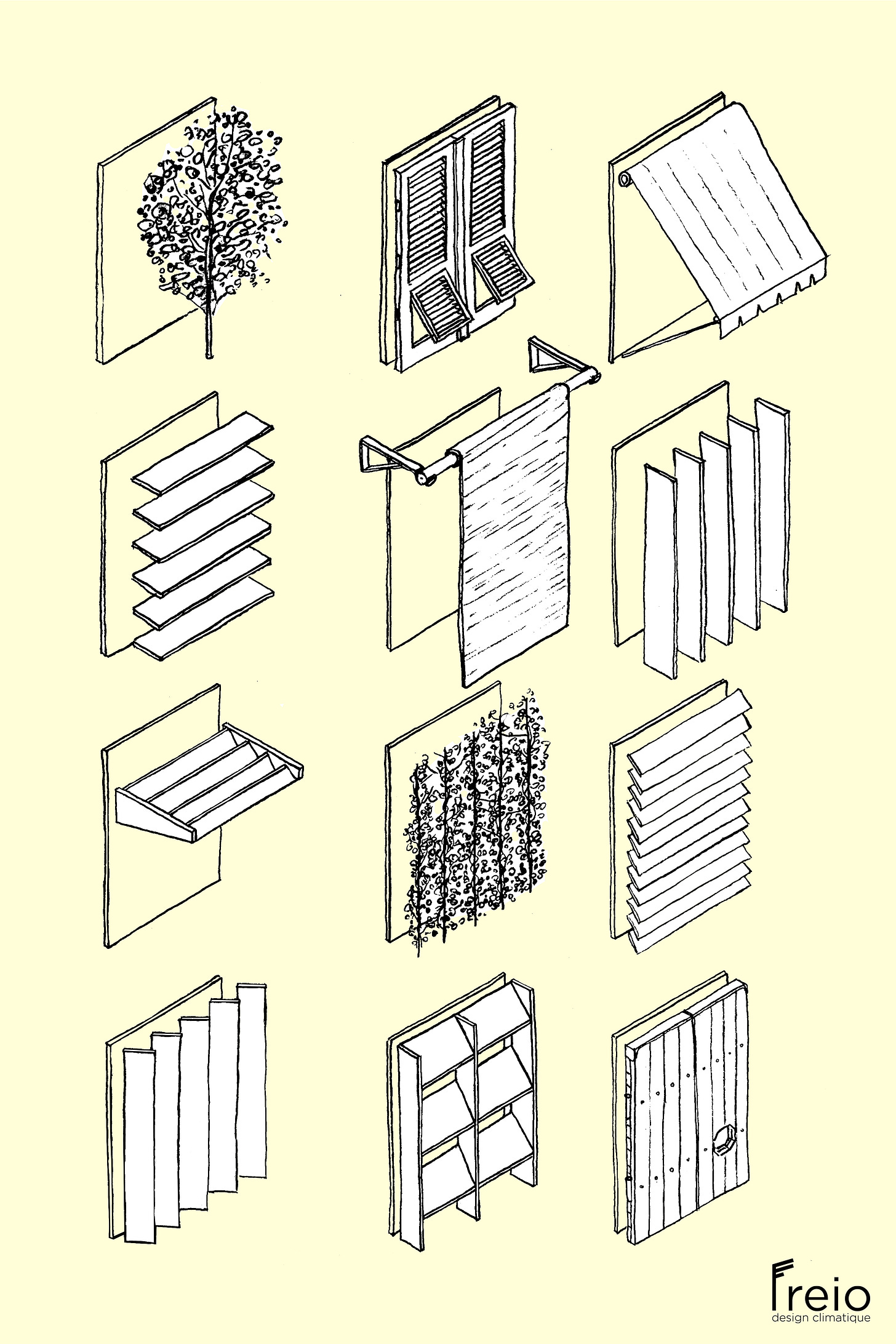

Long-forgotten images of familiar streets captured rows of windows adorned with awnings or shutters – and shop fronts draped with huge swathes of fabric as though they were Middle Eastern bazaars.

As Gaillard stared into the past, he realised that something had been lost. “When AC was developed […] all the shading systems were removed,” he says. “People thought, ‘We have AC, we don’t need shading anymore’ – but it’s a shame.”

Classic methods of window shading don’t just keep interiors cool during heatwaves. If done well, they can improve the aesthetics of cities, too, argues Gaillard. Now, he is on a mission to repopularise these old techniques because, he says, they could help people survive climate change.

Extreme heat is notoriously harmful, and increasingly deadly. Air conditioning, a form of active cooling, is growing in popularity as a result – and, undoubtedly, it will save many lives – but there are passive ways of keeping your home or workplace cool, which don’t require electricity. External window coverings are a prime example but there’s also special window coatings, smart glazing that reacts to sunlight – and even yoghurt. Bear with me.

Unpleasant under glass

Solar gain in buildings occurs when radiation from the sun warms up a building’s fabric. Crucially, glazing allows that solar radiation inside – but also helps to trap it there (the greenhouse effect). So, on a sunny day, big windows that face the sun can raise indoor temperatures by many degrees. Architects sometimes harness this effect to reduce demand for active heating on winter days. But the flipside is the need to avoid excessive solar gain overheating a property during hot weather.

When successive heatwaves struck France in recent months, Gaillard pulled down the awnings that shade the windows of his own Montpellier apartment, in the sun-baked south of France. “They are plastic – not very beautiful,” he says of the window coverings. While they helped, with daytime temperatures exceeding 40C there were still some nights when he found sleep tricky.

He suggests that even more comprehensive use of shading could make life in heatwave-troubled cities more bearable, though. There’s a French term for hunkering down in a shady property, he says: “Se mettre en cabane” or “S’encabaneur”, which roughly translates to locking down or putting someone in jail. The more positive spin, that this is an act of defiance, or resilience, is sadly lost in translation.

In any case, Gaillard has designed a range of attractive window coverings inspired by old techniques: “If you want to promote the heritage of a city, look at how the city was protected in the beginning of the 20th century – we had much more solar protection, much more shading of streets than today.” Awnings have disappeared en masse in many other countries, including the UK, as noted by Robyn Pender at Historic England, a body that advises the government on heritage properties.

People are sometimes resistant to such forms of passive cooling, however, says Gaillard. These systems generally require the homeowner to physically set them up when a heatwave looms. “It’s easier to just control the temperature using the remote for your AC,” he laments.

Plus, there are other considerations. In very windy weather, large awnings could be at risk of collapse and might require additional support.

Whey cool

Perhaps the strangest approach to reducing solar gain I’ve ever heard about is that of spreading yoghurt on one’s windows to create a sort of frosted glass effect. This can reduce indoor temperatures by a few degrees, according to a researcher in the UK. Allegedly, the yoghurt has no smell once dried and is easily washed off at the end of summer. I ask Gaillard if he has ever heard about this technique and he says he has not, though he does mention a limestone powder called blanc de Meudon, or Meudon’s White, which he says some people in France use to whitewash their windows in order to achieve a similar effect.

Alternatively, increasing tree cover in urban areas can reduce temperatures at ground level by as much as 12C – though excessive tree cover can also trap heat in urban areas at night, according to a recent study. Another approach is to use jaalis: external perforated or latticed wall structures that allow some light through but not all. This is popular in India, and appears in both ancient and modern architecture.

Scientists are coming up with some extremely clever, though much more complicated options, too. A paper published in the journal Energy and Buildings this month describes a thermochromic hydrogel – which reacts to temperature, becoming reflective or opaque – allowing windows to automatically reduce solar gain during high temperatures. In tests using a box, not a full-sized room, the technology allowed plenty of light through but kept internal temperatures 10C lower than in a version of the experiment that used traditional glass only.

There are other ways of making smart windows and it’s worth noting that double and triple glazing also reduce solar gain compared to single glazing. You’ll see this measured in terms of g-value on glazing – a really good triple-glazed pane might have a g-value as low as 0.4. Single glazing has a g-value almost double that, of around 0.86.

Gaillard is less interested in high tech glazing and smart windows, though. He pines for traditional, low-cost, aesthetically interesting solutions. It reminds me that the people who work in climate adaptation often possess a drive – a conviction – that a particular idea or approach is worth pursuing. Physics matters, but passion gets things done. That’s something I frequently sense when I speak to engineers and designers about things like this. Gaillard is no different.

Occasionally, he finds himself scouring the web for more old photographs of shutter and awning-peppered buildings. It’s “mind-blowing” to see, he asserts. They just worked, didn’t they? “For me,” says Gaillard, “The simpler the system, the better it is.”

Further reading on this week’s story

In June, the fantastic publication Low Tech Magazine published a story on “how to dress and undress your home”, exploring historical applications of textiles in dwelling spaces. This included, in part, methods of shading a building’s openings or windows. Plus, there’s a follow-up. One reader of that article was inspired to make and install a DIY awning on their own balcony, in a German apartment building. They documented the results and, in July, Low Tech Magazine shared details and pictures of the setup.

There’s an interesting opinion article about the usefulness of trees and hedges for urban shading in New Civil Engineer this week.

Update: Added a link to an article by Robyn Pender.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this story, don’t forget to share it with your friends and colleagues. You can also subscribe to The Reengineer and follow me on Bluesky.

Good Morning,

This article makes an excellent point. Thank you. This is just to add that *internal* blinds and curtains can also be effective at reducing solar gain. The create a "pool" of hot air between the blinds and the window and heat only leaks into the dwelling at a much lower rate. This is particularly true for insulating blackout blinds - they have a metal foil to stop sunlight and a hollow hexagonal structure to trap air.

In any case, best wishes

Michael