What I saw at Octopus’s heat pump factory

Northern Irish manufacturing is part of the drive to decarbonise heating

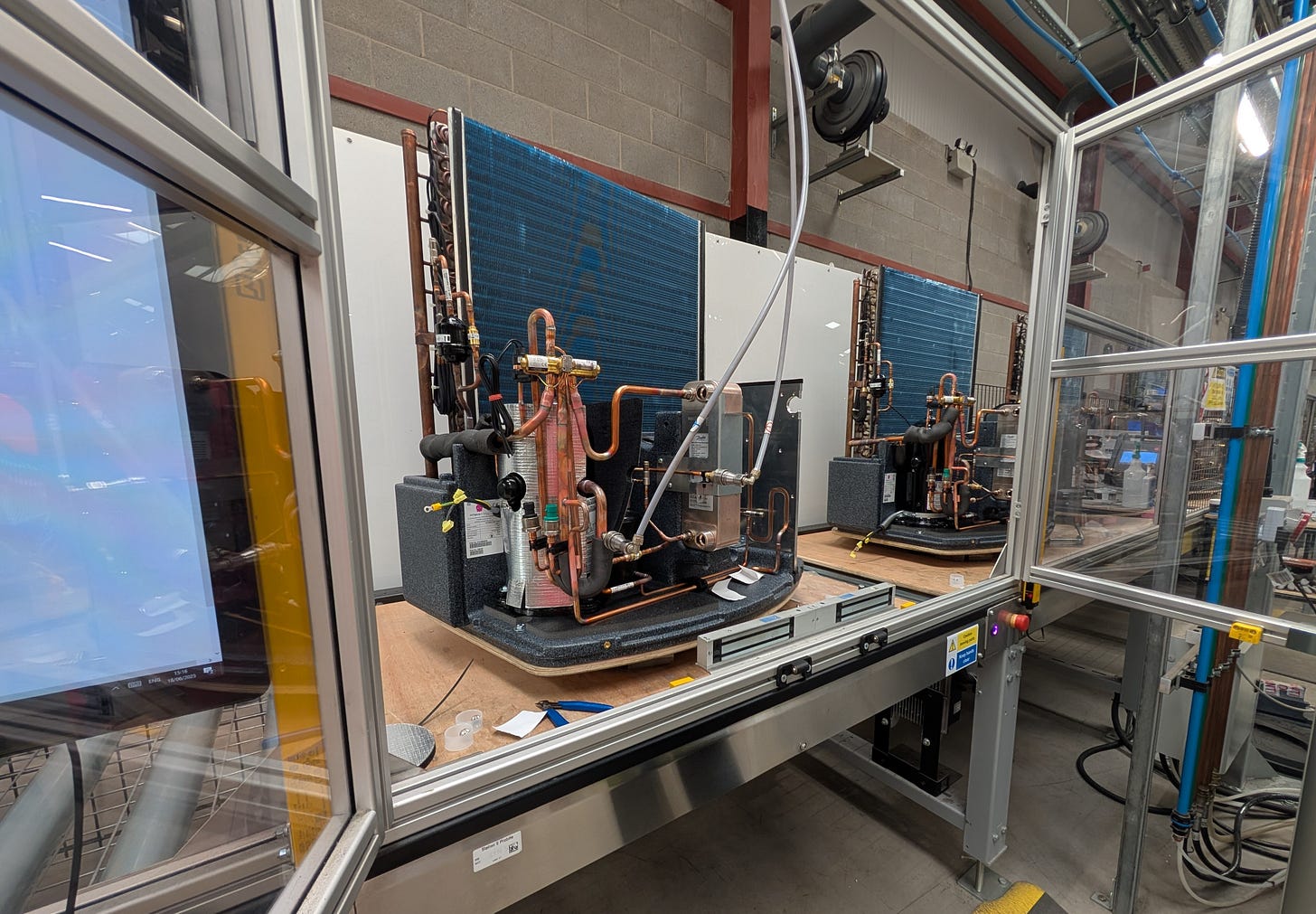

They’d bought the factory. Now they needed to ramp things up. In early 2022, Octopus Energy acquired a heat pump factory in Craigavon, Northern Ireland. But they wanted it to work harder – and churn out heat pumps faster.

“We were building at most one heat pump a day in a very workshop-like environment,” Mateusz Dewhurst, director of manufacturing, told me when I visited the factory for BBC News last month. The facility, previously owned by heat pump maker Red, soon got a new production line. Plus, it would switch to producing a heat pump of Octopus’s own design – intended for rapid assembly.

Back in 2022, Octopus aimed to ramp up production to 1,000 heat pumps per month by the end of the year. When I visited, however, the factory was churning out 600 per month. A second line is now in operation, Octopus says, which should increase production to around 1,200 units per month.

Octopus is unusual in that it is building, installing and monitoring its own heat pump devices – as well as selling electricity to customers. Other heat pump manufacturers are working with energy companies, though, and some might question whether Octopus’s approach is really necessary.

Heat pumps have been around for many years. They’re a well understood technology. Shouldn’t you just be able to grab one off the shelf, get it installed, and expect good results? You don’t buy your fridge from your electricity provider, after all.

Octopus and others would probably say that heat pumps are different. Installing and running them efficiently is trickier than with many other domestic appliances. The firm appears determined to prove to a sceptical nation that heat pumps are both reliable and cost-effective alternatives to fossil fuel-based heating systems.

Show and tell

I first asked Octopus about visiting their 30,000 sq ft factory, which is not very far from where I live in Belfast, back in 2023. But it was only in June of this year that journalists were allowed in – happily, I was one of them.

There were some details about the manufacturing process that didn’t make it into my BBC News story but I’m able to share them with you here.

Making a heat pump today generally means finding a way of cleverly assembling components largely provided by third-party suppliers. There’s no need to make your own compressor, for example – the bit that compresses air-warmed gas within the heat pump, in order to raise its temperature.

In Octopus’s case, they use compressors made by US firm Copeland, who also have a factory in Northern Ireland. Though, curiously, the compressors Octopus uses are first shipped to a fulfilment hub in Aachen, Germany before they make it to Craigavon. “We’re sorting that one out,” Dewhurst says.

From start to finish, Octopus’s production line covers the entire process of fitting components to the base of the heat pump casing, through pipework and cabling, leak tests, software and operation tests, and packaging. They are literally driven out of the door on the back of a truck as soon as they are ready, and delivered to distribution hubs elsewhere.

The pipe line

One of the stations on the line involves induction brazing, in which a worker holds a claw-like device over two pieces of connecting pipe. The claw floods those pipes with electromagnetic radiation, heating them until they are white-hot so as to fuse them together.

There are leak tests with helium gas to ensure the pipework that carries the refrigerant inside the heat pump is sound. “It’s more sensitive than three grams of refrigerant per year leaking,” Dewhurst says. I ask whether the workers ever find leaks that require repair, and he says they do – though declines to say how often. In many cases, though, the fix might be as simple as reheating a pipe joint with the induction brazing tool one more time.

In an attempt to maximise efficiency, the heat pump casings contain insulation beads. Exactly the same beads used for cavity wall insulation. And Octopus has come up with a metal plate that it says removes and recovers heat from internal electronics.

The firm uses propane, also known as R290, as the refrigerant in its heat pumps. R290 has far lower global warming potential compared to many other refrigerants and is also reasonably efficient even when the heat pump provides flow temperatures of around 60C.

Octopus’s Cosy 6 and 9 heat pumps are rated to supply maximum flow temperatures of 70C, which would not be the most efficient way of running the device – but it does mean that they have a wide range of operating temperatures. That kind of flexibility is something that could help heat pumps achieve wider adoption, though some would argue it is better to run heat pumps at the lowest possible temperatures, in order to reduce carbon emissions and energy consumption.

One thing to consider when using R290 as a refrigerant is that it is highly flammable, and potentially explosive. That’s why leak testing is so important. The factory checks for R290 leaks while the heat pump is loaded with this gas. I’m shown a device that constantly sniffs the air for traces of R290. If it detects as much as 30% of the lower explosive limit – the minimum concentration of gas that would burn in air – then the process shuts down and alarms go off. There are also heavy-duty ventilation systems on the floor that can remove the R290, which is heavier than air, in the event of a build-up.

A good run?

There is an app so that customers can track the coefficient of performance, or Cop, of their heat pump. This is a measure of how much heat, in kilowatt hours, the device produces for every kilowatt hour of electricity it consumes. An extremely well installed heat pump might have a seasonal Cop, or Scop (which is measured across one year of operation), of 4 or more.

Octopus monitors the running of its customers’ heat pumps centrally and can tell when they’re not operating as well as they should. A Scop below 3 would mean that the heat pump is probably costing a household noticeably more to run than a gas boiler. This is because of the “spark gap”, which refers to the relatively high cost of electricity per kilowatt hour versus the cost of gas per kilowatt hour. So, how your heat pump is installed – and how you use it – really matters.

“You see a lot of people get a heat pump and then try to run it like a boiler – and that will result in a lower Scop than probably they were promised,” says TJ Root, Octopus's Cosy program director. In other words, if you try to whack your heat pump on for a few hours here and there to boost heat in your home, it’s going to run harder than it needs to and cost you more. But, generally speaking, if you allow it to gently top up heat over a longer period, then it will be much more efficient.

Root explains that Octopus has intervened with customers in such cases, to help them get the best results from their install.

There are fans of air-to-air systems out there. These devices transfer heat from outside air by blowing it inside, like an air conditioner, rather than distributing heat via water-filled radiators. When I ask about this, Root acknowledges the value in such systems being able to provide cooling during the summer months, though he argues that the UK market at large is better served by air-to-water systems.

“[Air-to-air] is only really efficient where you have central ductwork,” he says. “[And] very few UK homes have an open plan architecture.”

Whatever flavour of heat pump you’re talking about, it all comes down to whether people are actually willing to buy one. There remain many myths out there about heat pumps – as well as legitimate concerns about achieving good installation quality, coping with maintenance issues, and lack of subsidies in certain areas including, yes, right here in Northern Ireland.

Heat pump adoption is growing – but manufacturers in the UK and around Europe could be making many more of these devices right now. The truth is, they are waiting for more demand.

Further reading on this week’s story

The Energy Saving Trust has a guide to heat pumps for UK homeowners and the Federation of Master Builders has reviewed various available models.

The Institute for Public Policy Research published a report last year on the economic potential of heat pump manufacturing in the UK.

You might also enjoy my other reporting on heat pump super-fans, the previously untold story of the rise of Heat Geek, the hunt for the most efficient heat pump in the world and the biggest heat pump projects in Britain.

Update: Clarified a quote about air-to-air systems.

Update: Corrected the detail on how many lines are operational in the factory.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this story, don’t forget to share it with your friends and colleagues. You can also subscribe to The Reengineer and follow me on Bluesky.

Thank you. I recently visited the offices (not the factory sadly) of ICAX.

https://protonsforbreakfast.wordpress.com/2025/07/22/icax-a-new-uk-heat-pump-manufacturer/

One feature that I heard about colloquially but have not had confirmed is that the very odd shape of the Octopus heat pump also includes so-called expansion vessels - saving space inside the home. Can you conform or deny?

Best wishes

Michael

Thanks: Interesting details and a great photograph.

Just to say, the unit of temperature - the degree Celsius - has the symbol °C. The symbol "C" without the degree symbol refers to coulombs - the unit of electrical charge.

Best wishes

Michael